I spent 43 days in Spain visiting lots of places north of Madrid and in Seville.

In 43 days, a lot of things can happen. One can almost complete a career as prime minister in that time.

For me, it represented a period which strengthened my understanding of how life is for Chinese people living in Spain.

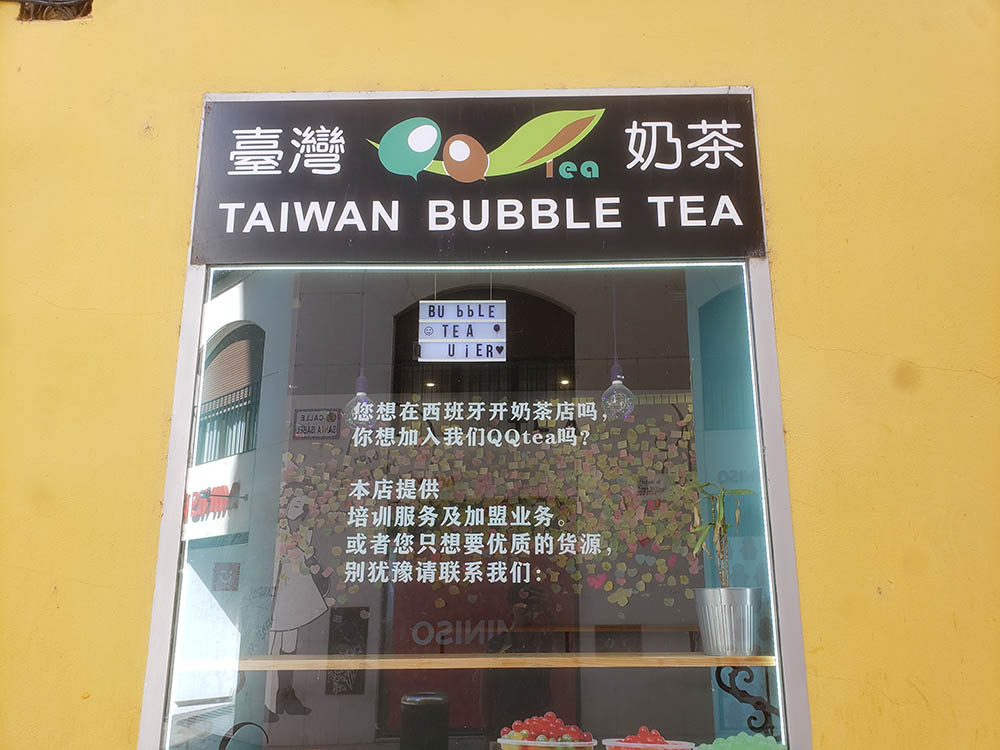

A “chino”: a dollar store or a restaurant

In Spain, you’d find a lot of tourist information kiosks and offices in every city. Tourists go there to get recommendations for places to visit.

And in almost every city, there will be a Chinese family running a chino. The bigger the locale, the more you’ll see.

We in the English-speaking world might find it a bit off-putting to call a type of store by the race of its owners, but in colloquial speech, c’est la vie in Spain.

Chinese restaurants are widespread in the world, so that’s no surprise. However, the “dollar store”, known as a bazar, represents a unique phenomenon that I have never seen anywhere else in the world.

In the UK, US, Canada and Germany, corporations run the dollar/euro/pound stores. You have Euroshop in Germany, Poundland in the UK, Dollarama in Canada and Family Dollar in the US.

However, in Spain, this industry is run by Chinese families.

In almost every sizeable town, you’d find someone selling stuff you’d find in a dollar store. Brooms, pans, butane stoves, wallpaper, fly swatters and other items for the home.

Nihao, laoban

In Spain, if you see an East Asian person and said “nihao” chances are you would probably receive a “nihao” in reply.

There was only once in Pamplona where I said “nihao” to a Korean girl and got nothing back. That’s exceedingly rare.

So why did I introduce the previous paragraph by telling you about tourist info centres?

I went into many Chinese stores and the first thing I would say is “nihao”.

In my experience, this established an instantaneous rapport with the folks running these stores.

I was going on a road trip and I needed to buy a bunch of stuff to furnish the car for camping. I am glad I went to a bazar. They have everything you need – window coverings, lighter fluid, funnels, spoons, etc.

A bazar owner in Matadero, Catalonia, was also kind enough to help me find things in their store that were aisles and aisles of stuff.

More than that, the warmth I received from many of these small Chinese businesses was overwhelming.

Finding Pei Pa Koa in Spain

In Seville, my friend, Paloma Chen, was having a cold and I told her that she should take some Pei Pa Koa. She told me she has never tried it.

I thought it was a very crucial Chinese experience and so I went out to buy it.

In Canada, I have no doubt that I’d be able to find it in a major city’s Chinatown. I wasn’t so sure in Seville.

In the second bazar that I went to, I received immense help from the mother-son staff. They were from Fuzhou.

The mother told me exactly where I could find it and the son told me what the name of the store was.

And this is not an isolated event. Throughout most of my interactions in Spain’s many bazars, I received a lot of assistance, direction and warm conversations.

Finding food on a Sunday

If you are from Canada, you might find it very odd to have grocery stores closed on a Sunday.

To further the point: the Real Canadian Superstore that I used to visit opens all its checkout lanes on Sunday. They advertise it with a large banner.

However, in Spain, most grocery stores were closed on Sunday. I was caught in Bagà, in the eastern Pyrenees.

It didn’t help that it was a small town with few options.

I went into a bazar to buy a lighter for my camping stove and suggested to the store owners that I was hungry and they acknowledged that there were no grocery stores open, but I could go to the only convenience store opened by a Pakistani.

The bazar is a Chinese-language tourist info booth

If you don’t speak Spanish, but can speak Mandarin, going to a bazar represents a good starting point for local knowledge.

If you start your conversation with a nihao, it feels like having a NEXUS card or Ryanair’s Fast Track. I’d recommend it.

Nihao, not Cantonese

The last time I visited Spain was in 2005, and I don’t remember seeing that many Chinese people. Perhaps it was because I wasn’t paying attention.

Either way, my understanding is that Chinese migration to Spain has picked up over the 17 years that have passed.

A bazar owner told me that the Chinese communities in Spain and Italy are the large because immigrating to these places were easier.

Unlike Chinese migration to the former British colonies, I didn’t experience the Cantonese-Mandarin divide I would experience in the UK or Canada.

Nihao worked very well. Everyone understood it. There’s no awkward silence like when you say “nihao” to a Cantonese speaker. Or there’s no awkward pause in a Chinese business where you’re not sure which language to speak and so you default to the local language.

A clustered origin from Qingtian, Zhejiang

When I spoke to Dalton Yap, he talked about this concept of bandwagon migration when we spoke about how Hakkas migrated to Jamaica.

I found it rather interesting that most Chinese people in Spain have origins in Qingtian, Zhejiang. It’s near Wenzhou, which is south of Shanghai.

I’m no academic, but I am going to bet you that there’s some phenomenon of batch migration here in the same way the Hakkas migrated to Jamaica.

After Qingtian, the biggest group of Chinese people came from Wenzhou, then Fuzhou and then it was a crapshoot.

Of course, these are just my observations and not statistically significant data. My friend who visited there at the same time said she found a lot of Guangdong people. I didn’t even meet one.

Even though this data is anecdotal, I’m going to bet you that if you asked five random Chinese people where they can trace their origins to, they’d say Qingtian.

Vamos al chino

I attended an event about culture and citizenship in Seville and I got to watch Vamos al chino for the first time. Translated to English, the show’s title means “let’s go to the Chinese (store)”.

Led by Xirou Xiao and featuring a full cast of women, Vamos al chino showed life of people working in a Chinese convenience store, their lives at home, family dynamics and poses questions about how Spanish society views them.

Not that I understood half of the dialogue – the questions were in Spanish and some portions were in a Chinese language that wasn’t Mandarin.

Luckily, the most poignant part of the performance centred around chaos. It’s quite a stark, shocking and perhaps depressing play.

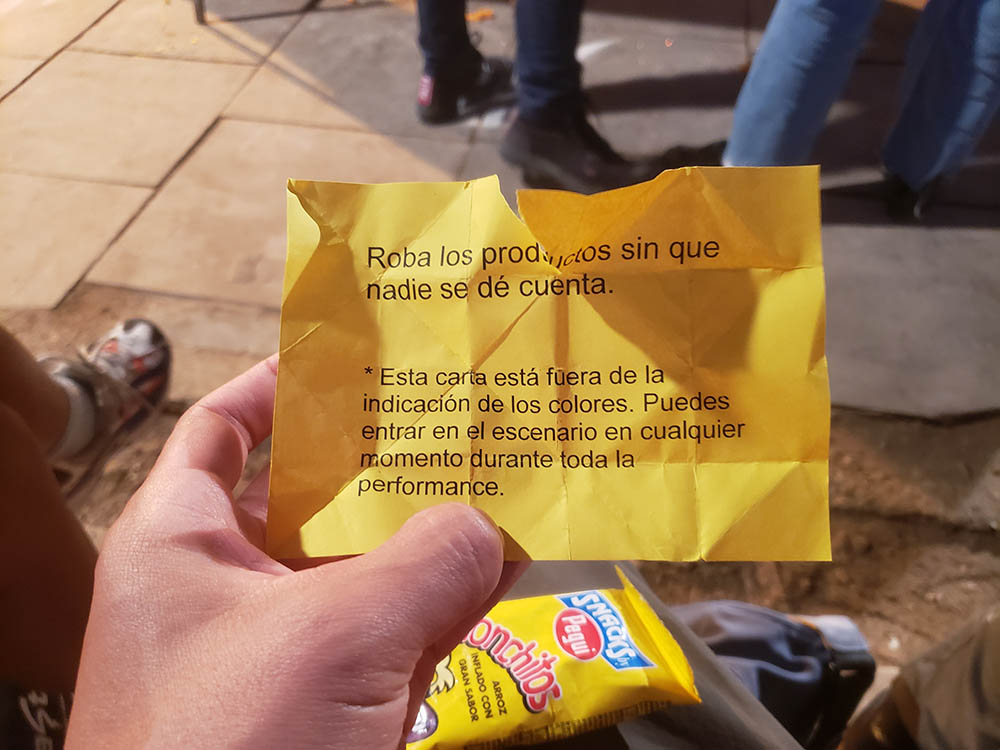

An aspect that the show wanted to exhibit involves how unruly customers are. Xirou personally passed the front-row audience an origami heart. After a few minutes, we were asked to unravel it.

At this point, the cast laid out a stall with different snacks.

This heart contained instructions to cause chaos. Mine, yellow in colour, asked me to steal an item from the stall.

Others were asked to take photographs (which the cast would protest), while others were meant to be rude, sweep the snacks off the table (causing loud protests from the staff) and more.

To culminate it, a member of the audience came by to flip the table. It was done right in front of me so much so that my feet could touch the table as it collapsed. I am not sure if this was a planned element because it felt rather hazardous. Either way, it sent the message of chaos.

After the show, I was left in complete disbelief. I questioned whether this is dramatization in the same way Walter White is dramatization dialed up.

I spoke to my friend, Paloma Chen, who told me that what I saw were real events. I couldn’t believe it.

If you are in a major city in Spain, I would recommend you look up Cangrejo Pro, Xirou Xiao or “Vamos al chino“. If you can’t find any info, feel free to email me and I will get you some help.

If you’re a Chinese person like myself who never had parents who owned a retail business, you might learn a lot.

A little video snippet of Vamos al chino

Here’s a 360 video. You can use your mouse or finger to move the camera around.

I assure you this does not contain any spoilers. This video is all calm and collected. The real heart of the play is all chaos and pandemonium.

Chinese names

In Spain, I found that people didn’t take up Spanish names and give up their Chinese names, unlike in the US or Canada.

For example, you have the whole cast of Vamos al chino having Chinese names only.

The photo above is a 360 photo which shows the cast of Vamos al chino. The performance is made up of Chinese women only. You can use your mouse/finger to move the camera.

Even people who were born in Spain might only have Chinese names like Quan Zhou (from Andalusia) and Run Xin Zhou (from Alicante).

What a phenomenon that runs against the grain of what’s happening in the English-speaking world.

Leave a Reply