What does “Chinese diaspora” mean and is it problematic to call ourselves that?

If someone on the street asked me if I belonged to the Chinese diaspora, I would wholeheartedly agree.

My understanding of the term is basically similar to the meaning of “Overseas Chinese,” someone who can trace their lineage back to China but live and perhaps grew up away from China.

However, I stumbled upon a Wikipedia article about a scholar named Wang Gungwu who seems to have a problem with this word. Here’s the relevant paragraph,

“He has studied and written about the Chinese diaspora, but he has objected to the use of the word diaspora to describe the migration of Chinese from China because both it mistakenly implies that all overseas Chinese are the same and has been used to perpetuate fears of a “Chinese threat”, under the control of the Chinese government.”

For introduction’s sake, Wang Gungwu is a China/Chinese migration scholar, although this summary might be too simplistic. Academics are great with their “yes and no” answers to everything that they should write a book called 100 Shades of Gray.

Checking the reference of the quote led me to a long interview.

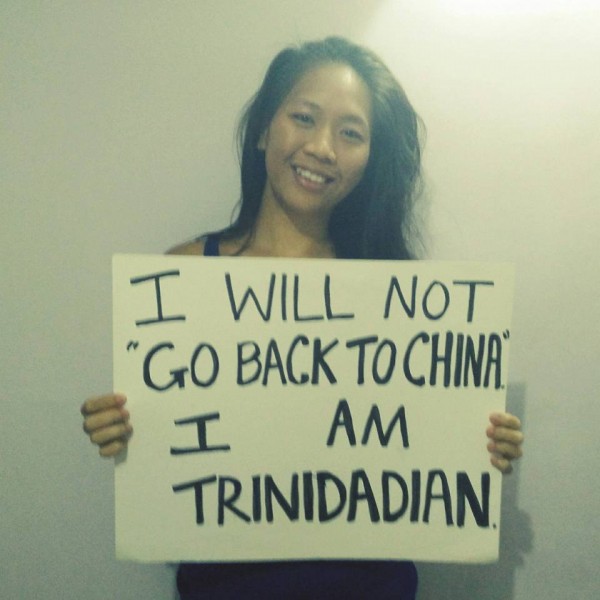

Indeed, Wang Gungwu’s disdain for the word comes from the implication that Chinese people are a monolithic unit. Meaning that, no matter where we are, we have the same beliefs and that we are all loyal to China.

It’s best summarized by the following paragraph,

“To assume that a Chinese is tuned to the mainland, implies that he knows their culture, he has connections at all level and knows what to do to, where and when. All these, just because he is ethnically Chinese.

“In fact, many overseas Chinese don’t know anything simply because they have not been brought up in a Chinese environment or in a Chinese way in China. Some of them may not know a single thing about the Chinese history.

“Think of the Chinese Americans, and the other people of Chinese origin anywhere else in the world. I don’t believe they have much to share in common. Of course, what remain is that they can speak Chinese and becomes an advantage if you are dealing with China.”

I have spoken to about seven sources at this point and my feeling is that, it’s true that most folks would identify with their nation first, rather than being “Chinese.” This is something Wang Gungwu did highlight.

There are shades of grey, though. What I have noticed is that some parents are much stronger in influencing their children in Chinese culture, while others don’t. In fact, Wang Gungwu himself had parents who made every effort to tell him about China and Chinese culture, according to his memoir. Besides about 18 months in Nanjing, the first 20 years of his life was spent in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) and Malaya (Malaysia).

A pertinent question I also hear from non-Chinese people is that Chinese people don’t integrate. I heard it from an Ecuadorian as I have read it in Paloma Chen’s blog about Chinese people in Spain.

Wang Gungwu believes stems from people conflating Chinese people’s affinity for our own culture as a political identification. He writes,

“Most of them identify themselves with the country where they live. A Chinese in Thailand is first of all a Thai. The confusion is that If you ask them, they tell you that they find it useful to learn Chinese to do business or, it is a way to regain some pride in their culture, to try to understand who were their ancestors. But such attitude does not translate into a political identification.”

He talks about how the European concept of a nation-state, which means that in order to be a full citizen, one must have certain characteristics to the exclusion of everything else. However, Chinese people might see more fluidity between these characteristics.

Chinese diaspora definition

There’s also another aspect to it. Wang Gungwu says that “diaspora” implies wealthy migrants who have a “business acumen and wealth.” Wang observed the migration patterns of the recent centuries and noted that most Chinese migrants were poor.

So, at the end of the day, Wang Gungwu wants us to stop using the term “diaspora,” assuming you agree with him. Here’s why,

“The word diaspora is in itself an oversimplification and I find personally very alarming that people talk commonly of a Jewish diaspora, an Indian diaspora or a Chinese one, as if the world consist of few ” leagues “. It is simply not true, but unscrupulous people can use such description to build up the image of a new yellow peril … with a lot of imagination, one’s could even end up saying: “The Chinese are coming, the Chinese are coming! “

“So, I would say that it has to be scrutinized, even from the scholars, I hope they will come out and say : Hey! That’s not what you mean, you use that word for this political purpose, that is not legitimate. Scholars must have to say that.”

What do you think?

Leave a Reply