Short of interviewing a person directly, I try to understand them through their words.

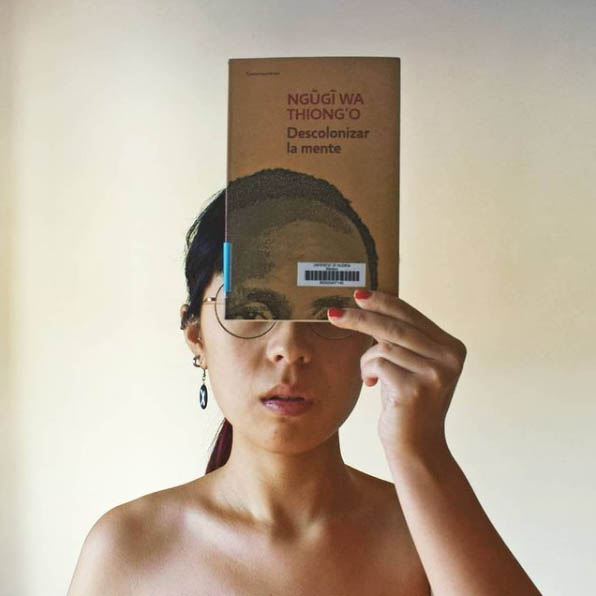

I encountered an interview with a 23-year-old Chinese person in Spain, Paloma Chen, in the Spanish newspaper El Pais. The first time I picked up El Pais was in 2005 when I lived in Salamanca, Spain, and picking one up in Mexico City brings a strong sense of nostalgia.

On a side note, I am a little amused that Spanish newspapers prefer long paragraphs while English-language news prefers succinct paragraphs.

Half of the article focuses on Paloma’s win at the Royal Academy of Spain (Real Academia Española) for her poetry. The other half talks about being a Chinese person in Spain.

Utiel, Valencia, Spain

Paloma Chen grew up between spring rolls, three-delights rice and sweet and sour chicken, at the Chinatown restaurant in Utiel (Valencia). Her parents had migrated from the Wenzhou region of China in the 1980s, like many other relatives and compatriots, and she was already born on the shores of the Mediterranean.

She was one of those girls who first play, draw and do homework at the last tables of the family business, and then, as teenagers, begin to lend a hand controlling the cash register or serving the tables. In Chinatown, the menu of the day cost 7.50 euros.

“I understand Chinese restaurants and bazaars as spaces of resistance,” she says, “they are places where migrant families try to prosper and where false stereotypes are reproduced: Chinese as synonymous with dirt and shabbiness.”

She dedicated her final degree project to this topic, entitled Crecer en ‘un chino’..

Paloma Chen: “El restaurante chino es un lugar de resistencia”, El Pais

Crecer en un chino translates to “Growing up in a chino.” I didn’t get what a “chino” referred to, so I asked a Spanish Basque friend and she told me that in her region it refers to any Chinese business, mostly dollar stores or restaurants.

Paloma’s blog is https://crecerenunchino.wordpress.com/

Paloma seemed to have the same issues of overseas Chinese with parents who were born elsewhere. She grew up wedged between Chinese culture and Spanish culture, being the only Chinese girl in town — probably something like Lily Kwok and also having language barriers with her parents.

“Of course we understand each other for everyday issues, but there are always deeper places where we cannot go,” she explains.

Paloma Chen: “El restaurante chino es un lugar de resistencia”, El Pais

Heck, although me and my mother were born in the same country, we always had a similar barrier because she spoke Chinese as her primary language and I spoke English as mine. That meant if we had something really technical to talk about, both of us would stumble. It wasn’t until I got off my butt to work on my Chinese did this divide amelioriate.

Paloma Chen fulfills the project that many migrants must conceive when they leave their countries: a first generation that arrives and sacrifices so that a second generation can master the language, go to university, integrate, win poetry awards and even recite in the Royal Academy.

The story of success.

“I am not very convinced of that story because, although there are cases, it does not always happen that way either. And although it seems that one integrates, they do not completely integrate either: there is what in the Chinese community we call the bamboo ceiling”.

Paloma Chen: “El restaurante chino es un lugar de resistencia”, El Pais

From my interview, the analysis of the author is quite accurate. From the interviews I have done, most Chinese migrants do the daily grind in their restaurants, groceries or other businesses. But there are a few that are luckier, such as Eric Yuan Jan in Peru, whose father moved to Peru as a Taiwanese expat in order to lead the Chinese school in Lima.

To that end, I see the parallels with a professor by the name Wang Gungwu. His memoir, Home is Not Here, talks about his family’s migration in the 1930s from Nanjing and Jiangsu. His parents were also intellectuals who were Chinese expats in Indonesia and Malaya. They led schools in those former European colonies and although they weren’t wealthy, Gungwu grew up in a much more erudite environment where he learned Classical Chinese.

It gave me the thought that where a person came from in China would have a significant correlation with what their starting point in a foreign land would be. It seems that Chinese people from the region near Shanghai (in Zhejiang, Jiangsu) have a higher prevalence of white-collar migrants.

In my small and non-conclusive sample size of interviewees, everyone who ended up starting a business had a Cantonese background, only Eric’s family didn’t. Eric’s father was born in Jiangsu.

We live in a time in which, not without controversy, identity politics, feminism, anti-racism, the claims of minorities have a strong weight in the public debate. Does the time accompany her poetry?

“In a way, the times are good, but I also have the feeling that when we step outside of certain bubbles, all of this is an illusion, that much more needs to be achieved.”

The members of this multicultural generation have been called “chiñoles”, a concept that, although Chen does not dislike it at all, it doesn’t quite convince her. “It is a term that gives way too much to jokes,” she says, “also, it gives the impression that we are people cut in half, 50% Chinese and 50% Spanish, and that is not the case either. It’s more complicated”.

Paloma Chen: “El restaurante chino es un lugar de resistencia”, El Pais

A few weeks ago, I attended a #StopAsianHate rally in Vancouver. That marked the first time in my life I have seen Asian activism. Elsewhere in the world, there’s #NoSoyUnVirus and #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus

I believe overseas Chinese people are developing a new identity. We can’t go back to China but in some people’s eyes, we’re linked inextricably with China. If we’re minorities, we have to contend with that challenge and it sucks.

As overseas Chinese, we are brought up based on local circumstances and the perhaps the imperceptible influence of being Chinese. Yet, it’s also hard to describe and delineate where it crosses over. Indeed, every time I ask someone about their Chinese background and their Mexican/Trinidadian/Peruvian/etc. background, I find that I never really get a clear answer.

Paloma’s blog is pretty interesting. It’s a bit like what I am writing, except focused on Spain and is written in Spanish. Take a look. You can also read her poetry here.

Leave a Reply