Wanrong Chen/ Liza Chen

陈婉容

Born: Taishan, Guangdong, China

Raised: Mexicali, Mexico

Are there threads of similarity between Chinese people?

The more Chinese migrants I meet, the less I am able to answer that categorically.

On the one hand, I’m just fresh off an interview with Roberto Cai Wu, whose parents were from Taishan, Guangdong, China.

Then, I met Chen Wanrong, also from Taishan.

Some parts of this interview will come with footnotes. That’s because we did this interview in Chinese, and sometimes, translating Chinese to English causes a loss in sentiment. If you want her response at its fullest, read the footnotes.

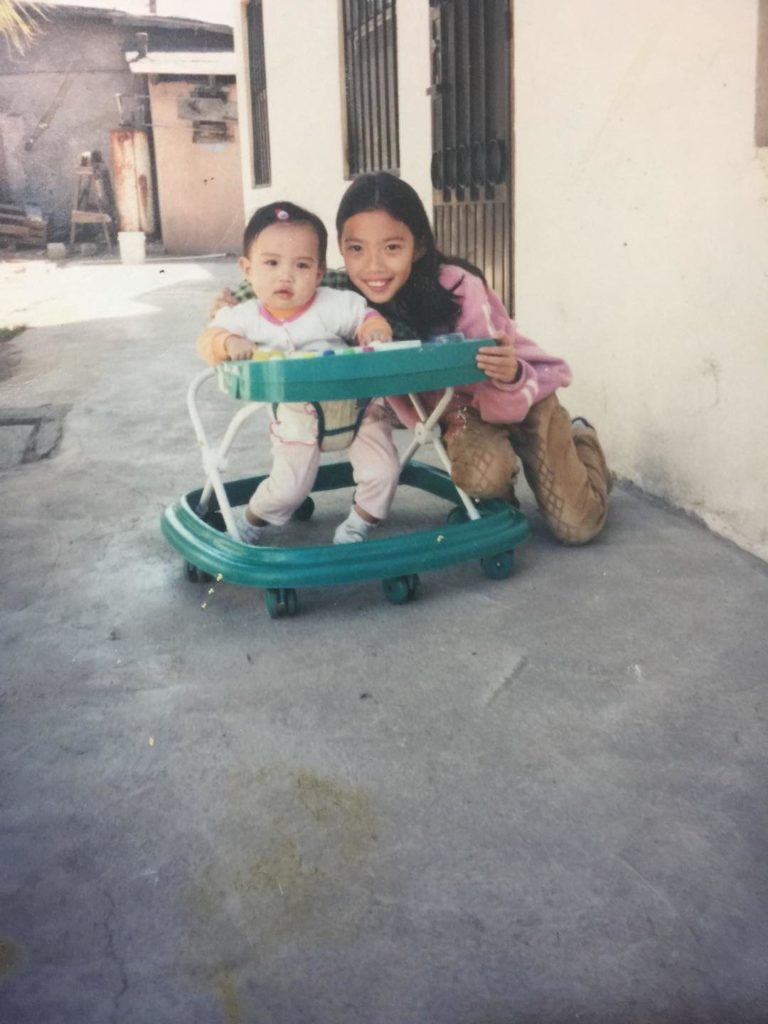

Wanrong is from Taishan, Guangdong, China. Her family moved to Mexico when she was seven years old.

In Roberto’s article, I asked the question, “If I told you that Mexico could offer a better quality of life than China in 1991, would you believe it?”

Chatting with Wanrong really elucidated that even around 2002, Mexico could offer a better quality of life than China could have.

And this is where I had a bit of a “let them eat cake” moment.

Why move to Mexico and not the U.S.?

The privileged dude that I am, I don’t get it. Look, I got lucky and had ancestors who migrated to a country who would eventually become quite wealthy.

I asked Wanrong why her family moved to Mexico instead of heading straight to the usual suspects like the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, etc.

Her response really put me in a faux pas.

“It’s simple and realistic. We had no money, so naturally we had few choices. In fact, Mexico was the only choice available,” she said.

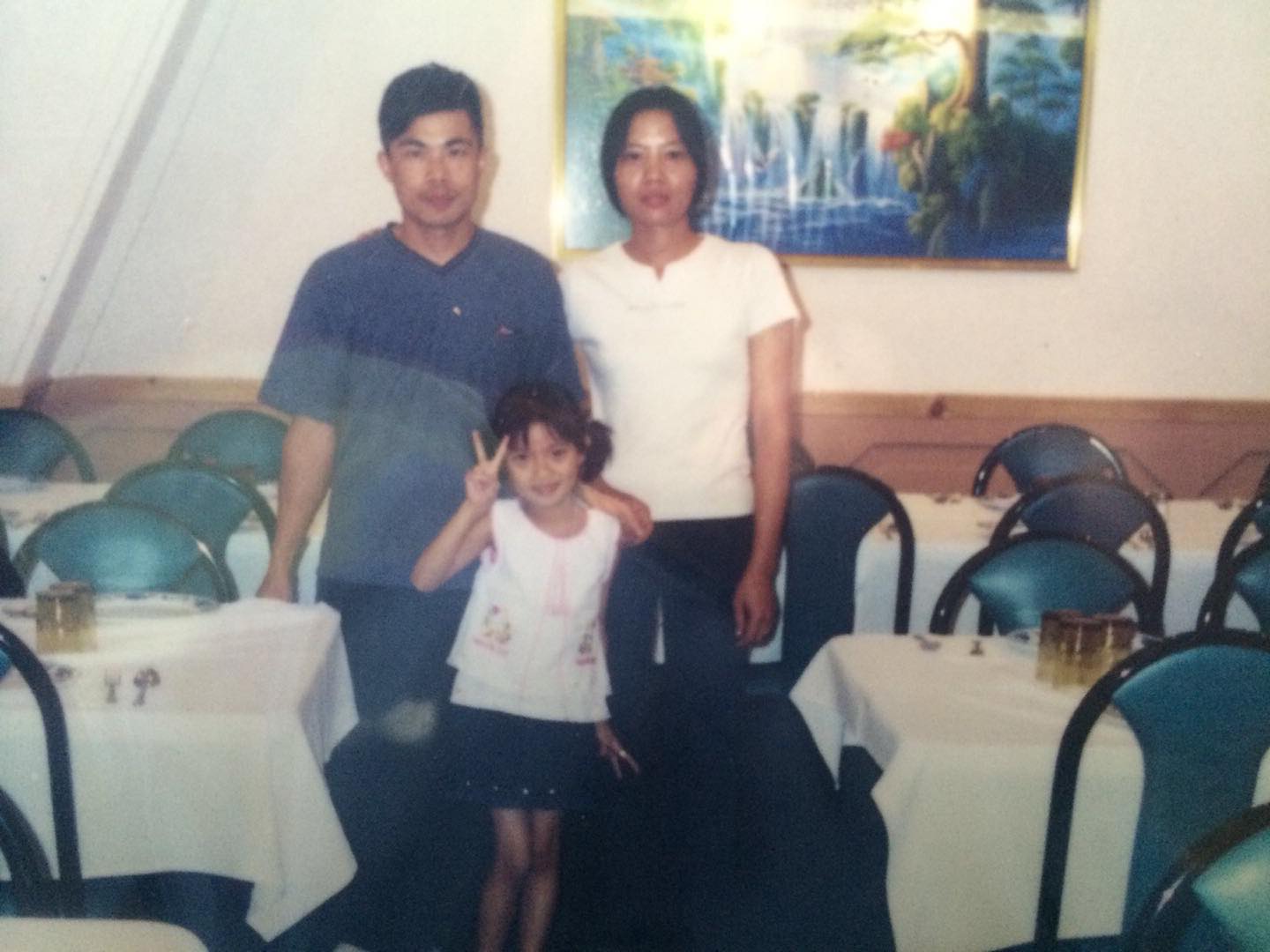

Wanrong said her family didn’t have the funds for her migration, so they borrowed it. The terms of the loan stated that her father needed to work at her relative’s restaurant until the loan has been repaid.

“Migration is brutal, and only first-generation migrants can fully understand it. At that time, Mexico had a better economy than right now, and although it might not be as good as other developed countries, it certainly was a little better than in China,” she continued.1

Finances aside, it turns out that the other reason why her family wanted to migrate was so that their family could stay together. Her father worked in construction in China and had to work away from home very often, and work opportunities were few and far in between, in addition to low pay.2

“Dreadful” living conditions

But before that could even happen, Wanrong and her mother had to endure one year of separation from her father, who moved to Mexico first before her and her mother.

In that one year, her father worked at her relative’s restaurant. Therefore, as a dea, those relatives helped him with the immigration process.

And so their family landed in Mexicali, Baja California, which is on the border with America’s California. Wanrong took on a local name from her aunt, “Lisa.”

She later changed it because she was bullied since “Lisa” in Spanish is the name of a fish, so she changed “Lisa” for “Liza.”

Unfortunately, it still isn’t happily ever after.

“As a young child, it was dreadful,” she said.

Wanrong lived with another family in her first house. She described her home as one built with cement and then expanded with lumber extensions due to the lack of space.

When it rained, the house would leak. The tenants couldn’t paint the walls, and so they used magazines and newspapers in order to protect the interior walls from rain.

Her neighbourhood was desolate and homes were abandoned and in disrepair.

“When I arrived, I had many complaints. I lived in poorer conditions than in China,” she said. “Insects roamed all over the floor, cockroaches, poor air quality, large sand particles and high temperatures. But I got used to it naturally over time.”

Luckily so, given that Wanrong clued in that this journey across the Pacific was a one-way journey.

She arrived at an inopportune time too. As she arrived a bit later than the cut-off for elementary school registrations, she could only go to school when she turned eight.

Being Chinese in a Mexican environment

As I stated in the introduction, I did this interview with Wanrong in Chinese.

We spoke a total of seven sentences in Spanish, then continued on in Chinese after she said that she prefers Mandarin as she’s better able to express herself.

I asked her how she managed to practise Chinese in such an environment.

She told me that the Chinese community in Mexicali is relatively large and there’s a Chinese association with a school that teaches Chinese. She attended Chinese school for a while before dropping out.

She learned the rest online, through online friends in China, surfing Chinese website, reading novels, movies and music. She learned Cantonese by watching TVB and then learned Mandarin through watching Taiwanese TV which led to her having a Taiwanese accent at that time.

Funny coincidence — I learned Spanish using the same method.

For Wanrong, learning Spanish meant starting from the alphabets, pronunciation, then tenses.

“After studying for one year, I started to slowly understand a few simple words used in school. By the time I was in fourth grade, I could communicate fluently,” she said. “Although these days I might still make grammatical errors or not understand some words.”

She said she has received bouts of prejudice before but she’s unsure whether it’s related to her being Chinese.

“At the start of high school, I was bullied by classmates, insulted by teachers, got hassled on the streets,” she said.

She added some taunts are more directly related to her being Chinese, including one where people called her a “dirty, disgusting Chinese person” who should go back to her own country.

When she rebuked those taunts, sometimes she would get dismissive responses like “just kidding” or more direct rebukes to her rebuke such as “you don’t understand humour, this is sarcasm.”

“Frankly speaking, some bad words and experiences have really brought a shadow to my childhood, although as an adult I have learned that sometimes I don’t need to care too much about others’ criticism of you, because they don’t know who you are, such comments are not important. but some harm has already been caused,” she said.

A restaurant’s scandal hits the Chinese community

Wanrong recounts the most poignant episode of racism that happened in 2015.

It started with a Chinese restaurant in Tijuana, a city in the same state, which was discovered eating dog meat.

I did some searching online and found a few sources that confirm that this happened. I also contacted the Mexicali Association of Overseas Chinese president, Ramon G. Yee, and he confirmed that it was a “highly commented incident.”

The best English source I found is the San Diego Union-Tribune entitled “Dog meat found in Tijuana Chinese restaurant.”

The article said that the scandal led to large losses of patronage towards Chinese businesses. China’s consul had to come out and say that the incident was an isolated case, “illegal and should be repudiated.” Chinese community leaders issued a statement condemning the incident.

“We are certain that the people of Tijuana have the judgment and the wisdom to not consider an individual event as the idiosyncrasy of all Chinese restaurants,” as quoted in the article.

Wanrong said that things were even worse. The news spread and this affected Chinese restaurants in other cities. She noticed that people refused to sell groceries at their local supermarkets; taxis and buses refused to pick them up and they were hassled on the streets with stones thrown at them.

I asked a previous interviewee, Eva Wong, about what her experiences were. Her family lived a few hundred kilometres away from Tijuana, so I just wanted to confirm that this incident spread throughout Mexico.

“Actually my family had a restaurant at the time. We think this was a big factor that made us close our doors,” she said. “Our customers diminished a lot after it happened. But at least for us or in our city, there was nothing violent as in throwing rocks at us.”

Ramon offered his view that the Mexicali community were very proud of their Chinese community and they experienced little racism besides isolated cases.

Going back to where you came from.

Wanrong went back to China once in all her 17 years in Mexico and she describes it as “strange yet familiar.”

She explained that the familiarity came from being born there and having everyone look similar, but it still felt like a foreign environment. Too much time away made some things really difficult to square.

“I felt disconnected with what’s happening in China, and I couldn’t keep up with the pace, but when I was in Guangzhou, besides the weather, I really liked that city,” she said. “The food suited my tastes, transportation was convenient.

“But payment could be inconvenient. I had to use WeChat Pay or AliPay to do that, and I couldn’t create an account so if the store didn’t accept cash, it would be very troublesome.”4

It’s no joke. Financial transactions in China are nothing like what we’re used to. Cash, debit card and credit card payment are all superseded by payment via a mobile phone app where you store money in your own account. It’s like Starbucks points.

Being Chinese. An advantage?

What Wanrong shared with me was that the Chinese community in Mexicali is actually quite developed.

She said that in Mexicali, people either ate tacos or Mexican Chinese food (comida china) to the extent that weekend family gatherings centred around eating Chinese food. She said that according to data collected in 2017, Mexicali had about 400 Chinese restaurants.

In her time in Mexico, Wanrong only worked in Chinese-owned companies. She said that as long as a person isn’t terrible at their job, a Chinese employer would be willing to hire another Chinese person.

“Between Chinese people, communication is easier. Language, habits, train of thought and logic might be much more similar,” she said. “Perhaps this is an advantage.”5

References.

Leave a Reply